John 1 according to the paragraphing of Greek manuscripts

Article

9th October 2024

Nelson Hsieh demonstrates in John 1 how the Tyndale House team will decide on paragraph divisions for the second edition of the Tyndale House version of the Greek New Testament.

Have you ever wondered where the Bible’s chapters and verses came from? Who created them and why? Chapters and verses do not come from the biblical authors. Stephen Langton created the modern chapter system in the thirteenth century, mainly to help his university teaching. Robert Stephanus later created the New Testament’s verse divisions in 1551, mainly to assist in reading the New Testament in Greek and Latin side-by-side.

Chapters and verses can sometimes distract or mislead since they impose a structure upon the biblical text that the original authors did not create. And sometimes the beginnings of chapters and verses are at odds with how the text itself is progressing.

Yet chapters and verses are still helpful navigational aids for easily finding and referring to passages in Scripture. But readers should regard them as the fallible interpretations of Langton and Stephanus.

This means that readers can feel free to disagree with the placement of modern chapter and verse divisions, and to subdivide the biblical text based on their own study.

New Testament scholar Grant Osborne says, ‘We should never depend on verse divisions for meaning. The paragraph is the key to the thought development of biblical books. [Readers should] skim each paragraph and summarize its main point’ (The Hermeneutical Spiral (2006), p. 41). Osborne provides good advice, but he does not sufficiently scrutinise the paragraph divisions in modern Bibles. Who decided where paragraph divisions should be placed? And what method and criteria were used to decide?

Editors have added paragraph divisions based on their own interpretation of the biblical text. Unfortunately, they rarely explain why and how they made these decisions. So readers need not automatically accept the paragraph divisions in their Bibles. They can arrive at their own paragraphing decisions. But how? What sort of methodology and criteria should be used?

Tyndale House’s New Testament research project uses two kinds of evidence for deciding on paragraphs. First, we study ‘internal evidence’ by examining the text itself. Second, we study ‘external evidence’ by considering how ancient manuscripts divided up the biblical text into paragraphs.

Making paragraphing decisions based on internal evidence

Internal evidence consists of the grammar and syntax of the text, focusing especially on conjunctions and other structuring devices. But paragraphing is also tied to literary genre. For example, most of John 1 is narrative, so transitional phrases should also be considered:

- Changes in time: ‘On the next day . . .’ (John 1:29,35,43)

- Changes in location: ‘On the next day Jesus decided to go to Galilee’ (John 1:43)

- Changes in speaker: ‘John answered . . .’ (John 1:26)

- Entrance/exit of characters: ‘There was a man sent from God, whose name was John’ (John 1:6)

One way to get a fresh perspective on Scripture is to begin with a ‘minimally marked text’. This is just the text of a Bible passage without any section titles, chapter and verse numbers or paragraph divisions. These textual divisions unconsciously—yet strongly—affect how readers perceive the structure of the biblical text. Modern printed Bibles all have these features, so readers can create their own minimally marked text by copying and pasting from an online Bible (such as esv.org).

Making paragraphing decisions based on external evidence

Ancient manuscripts are a valuable window into textual divisions that existed only a few hundred years after the New Testament was written. In rare cases, ancient manuscripts might even preserve textual divisions that the biblical authors created. Most readers are not able to look at these manuscripts for themselves, so here I give a glimpse behind the scenes of our research at Tyndale House.

Modern biblical scholarship has tended to identify textual divisions solely based on the internal evidence of grammar and syntax (as discussed above). It has generally neglected the external evidence of how manuscripts divided up the biblical text.

However, external evidence is not straightforward. The manuscripts often disagree with one another. On the Tyndale House research team, we don’t just count how many manuscripts support a textual division and follow the majority; we also judge the quality of specific manuscripts, and give more weight to some of them. And the external evidence must be weighed against the internal evidence before making a final decision.

Even if we decide to go against the textual divisions in ancient manuscripts, at least we have consulted the manuscripts, giving them a seat at the table and a voice in the discussion about how biblical texts are structured. In other words, we neither neglect the manuscripts (as much of modern biblical scholarship has), nor uncritically follow the manuscripts by giving them final authority.

Paragraphing in John 1

Let’s see how internal and external evidence helps us divide John 1 into paragraphs.

Internal evidence

There are obvious textual divisions in John 1. The phrase ‘on the next day’ occurs three times (1:29, 35, 43) and separates out three stories. The phrase ‘on the third day’ at John 2:1 also indicates a new story. John 1:19 provides a different kind of time marker: ‘And this is the testimony of John, when the Jews sent priests and Levites from Jerusalem to question him.’ Based on these time markers, John 1:19-51 divides into four episodes: verses 19-28, 29-34, 35-42, and 43-51.

Within each of these episodes, English translations differ on how to divide the dialogue into paragraphs. For example, in John 1:19-23 there are eight changes in speaker, but should each change be marked as a new paragraph? The English Standard Version (ESV) translation has John 1:19-23 as one single paragraph, whereas the New International Version (NIV) has seven and the Christian Standard Bible (CSB).

The paragraphing of dialogue is mainly a stylistic choice. Changes in speaker can be represented by sentence divisions with question marks and full stops, or these changes could be represented more prominently with paragraph divisions.

However, I said ‘mainly a stylistic choice’ because the Greek New Testament sometimes indicates emphasis by using the ‘historic present’ tense. Readers expect past events to be reported in the past tense, but Greek sometimes uses the present tense to report past events. Steven Runge has argued convincingly that the historic present highlights specific events or speech within the larger narrative (Discourse Grammar of the Greek New Testament (2010), pp. 125–43). A new paragraph division could be used to indicate the emphasis created by the historic present.

Those who cannot read Greek can still see the use of the historic present by consulting the New American Standard Bible (NASB). The NASB indicates the historic present with an asterisk (*) in the text.

In John 1, the historic present occurs seventeen times (in verses 15, 21, twice in 29, 36, 38, 39, twice in 41, twice in 43, twice in 45, 46b, 47, 48, and 51, and possibly also 49 in a textual variant). Some of these historic presents could be highlighted with new paragraph divisions.

The first eighteen verses of John 1 are more difficult to divide into paragraphs because this section is not narrative. The most popular option is to create new paragraphs at verses 6, 9, and 14. But the Greek manuscript tradition of John 1 suggests different ways of structuring John 1:1-18.

External evidence

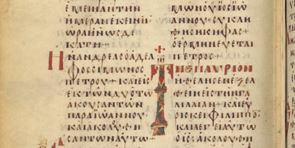

I have gathered paragraphing data from thirteen manuscripts dating from the third to the tenth century (Gregory-Aland manuscripts P66, P75, 01, 02, 03, 04, 05, 07, 011, 017, 019, 032, 1424). Codex Vaticanus (03) also has a numbered chapter system in its margins.

We observe the following in these manuscripts:

(1) Paragraph divisions at John 1:1, 6, 29, 35, 43 are nearly unanimous among the manuscripts. This isn’t surprising since these are obvious places for textual division with the introduction of John the Baptist (1:6) and the time marker, ‘On the next day . . .’ (1:29, 35, 43). Paragraph divisions at these locations might even go back to the apostle John himself.

(2) There is substantial disagreement on how to paragraph the dialogues in John 1:19-51. Some later manuscripts (07, 019) create new paragraphs for nearly every change in speaker (like the NIV and CSB translations), while most manuscripts seem to selectively choose some dialogue for emphasis. But three early manuscripts (01, 02, 03) agree on paragraphs at John 1:38, 41, 48b (‘Jesus answered . . .’), and 50. The historic present is used in 1:38 and 41, which lends support to having a new paragraph at these two verses.

(3) The paragraphing of John 1:1-18 in the manuscript tradition is quite different from modern understandings of this passage. Modern biblical scholarship is basically unanimous in considering John 1:1-18 as the ‘Prologue’ of John, which requires a major break at verse 19. So it is surprising that the earliest manuscripts (P66, P75, 01, 02, 032) disagree by not having a new paragraph at verse 19.

Oddly, from our modern perspective, many early manuscripts (02, 03, 04, 032) have a new paragraph at verse 18. And the ancient Synaxarion lectionary assigned John 1:18-28 as the reading for the second day after Easter.

Internal evidence supports a new paragraph at verse 18: the word order is emphatic (both the subject and object precede the verb). Modern paragraphing habits usually don’t create new paragraphs based on word order, but ancient paragraphing habits sometimes used word order to decide new paragraphs.

If verse 18 begins a new paragraph, its theological point becomes more prominent: Jesus alone reveals the invisible God.

(4) Modern scholars and translations are also nearly unanimous in having a major break at John 1:14 (‘And the Word became flesh . . .’). But the early and later manuscripts are nearly unanimous in having a paragraph break at verse 15 (‘John testifies . . .’). Internal evidence supports this paragraph break at verse 15: there is emphatic word order (subject before verb) and verse 15 has the only use of the historic present until verse 21.

The other paragraph division with nearly unanimous manuscript support is John 1:6. And what do John 1:6 and 1:15 have in common? Both describe John the Baptist’s testimony about Jesus. With new paragraphs at verse 6 and 15, the Greek manuscript tradition rightly highlights the role of John the Baptist’s testimony about Jesus within the structure of John 1:1-18. And this theme of John’s testimony continues in 1:19-28, 29-34, and 35-42. All three of these stories begin with John the Baptist, whose testimony explains who Jesus is and what he has come to do.

Conclusion

By closely examining the biblical text and carefully evaluating how manuscripts divided the biblical text, readers today can gain new insights into the Bible’s structure and what the biblical authors wanted to emphasise. Not every Bible reader can do all this, but everyone can give more thought to textual divisions, and not automatically accept the divisions in our printed Bibles.

Nelson Hsieh is Research Associate in New Testament Text and Language at Tyndale House