From the hands of scribes

Article

31st May 2021

How does handwriting shed light on variants in Bible manuscripts? Beth Vickers and Dr Dirk Jongkind take a look at how researchers read the clues left by the copyists.

Compare your handwriting with your grandmother’s. How different are they? Now compare your grandmother’s handwriting to the Magna Carta documents. You can tell a lot from a handwritten script. Without even reading the contents you can probably guess how old the document is, whether it’s an 800-year-old legal charter or a birthday card written by someone born in the early part of the 20th century. The idiosyncrasies of these different scripts tell us something about the person who wrote them and when it was that they put pen to paper or quill to parchment.

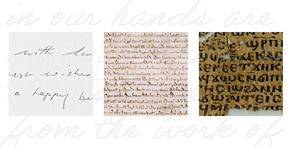

For centuries the text of the Bible was copied by hand, and it is the handwriting of the scribes who produced it which give us some of the best information about the oldest manuscripts we now have.

What do scribal hands and habits tell us?

The handwriting we find on ancient and medieval manuscripts is quite different from our handwriting today. Some of us may have been taught to write in cursive or may have come across a form asking the the filler to “PLEASE PRINT IN BLOCK CAPITALS”, but day-to-day we rarely come across specific handwriting styles. Ancient and medieval manuscripts, however, were produced in handwritten styles closer to modern typefaces or fonts than our own free-form approaches to handwriting. These book-hands, or scripts, were made up of specific character forms that created uniform text. One of these scripts is called “biblical majuscule” (also known as biblical uncial). It consists of uppercase letters made of simple curved strokes and named after its use in the big Bible manuscripts from the 4th and 5th century.

Another script we find in Bible manuscripts is called minuscule, a lowercase, joined-up script, closer to our modern way of writing, which came into use later than, but overlapping with, biblical majuscule. Most of the New Testament manuscripts which we have today were written in Greek minuscule.

While an individual scribe will write in a particular “font”, the words they produce on the page will still show small individual characteristics. There are also other types of evidence of scribes’ particular ways of practising their craft which get left behind in their manuscripts, and these are known as scribal “habits”. For example, scribes may have their own set of preferred abbreviations, and even have a specific weakness for making a particular copying error.

The study of scribal hands and habits forms part of the discipline of textual criticism, which broadly attempts to find a way through copies of texts to the most accurate version. Identifying the individual scribes helps researchers to find where they may have made errors or deliberate changes to the text. The work done by textual critics over the years to identify different scribal hands and habits in ancient Bible manuscripts contributes directly to the printed, translated Bibles we read today.

The hands that wrote Codex Sinaiticus

In 1846 Constantin Tischendorf, a professor of theology at Leipzig University, brought 43 leaves of an Old Testament manuscript from Egypt back to Leipzig. Originally published as Codex Friderico-Augustanus, the leaves eventually came to be known as part of Codex Sinaiticus. Written in Greek, in biblical majuscule script on large sheets of parchment, the manuscript would most likely once have comprised the entire Bible but is now incomplete, missing a large part of the Old Testament. What survives is half of the Old Testament in Greek (known as the Old Greek or Septuagint), the complete New Testament, the Deuterocanonical books (such as Maccabees), and the New Testament apocryphal books the Epistle of Barnabas and parts of The Shepherd of Hermas. Dated to the 4th century, Codex Sinaiticus is the oldest known manuscript of the entire text of the New Testament and one of the oldest surviving and most complete early copies of the Bible.

Tischendorf had found the manuscript in St Catherine’s monastery, which houses one of the world’s oldest working libraries and sits at the foot of Mount Sinai (after which the manuscript is now named). In 1859, 13 years after his first publication of leaves from the codex, Tischendorf returned from a third visit to the monastery at Mount Sinai, this time carrying the majority of the manuscript. He went to St Petersburg and there published its contents in 1862. The Russian government sold the manuscript to the British Museum in 1934, and since 1999 the manuscript has remained distributed across two continents, the largest portion being held in the British library, with other parts still remaining at Leipzig University, the Russian National Library and St Catherine’s monastery.

There is little known about the manuscript’s origins and history before it found its way into Tischendorf’s hands. Two scholars, H J M Milne and T C Skeat, produced the first book-length study of the codex in 1938. Entitled Scribes and Correctors of the Codex Sinaiticus, Milne and Skeat’s book argued that the whole manuscript was copied by three different scribes. Tischendorf himself had thought there were four scribes (A, B, C and D) and a number of extra correctors. Milne and Skeat based their argument on the handwriting in the manuscript. While the scribes used the same script (biblical majuscule) the researchers identified three individual scribal hands, known as scribes A, B and D.

Dr Dirk Jongkind, who was curator of the British Library’s Codex Sinaiticus Digitisation Project before becoming a Vice Principal of Tyndale House, has spent a lot of time with Sinaiticus. His book Scribal Habits of Codex Sinaiticus, focuses on the three scribes and their scribal behaviour or habits, their cooperation or collaboration, and their characteristic copying errors. The careful eye of the text critic is able to uncover evidence of the three scribes sharing out the tasks and responsibilities involved in creating Codex Sinaiticus, with various hands producing certain pages and correcting others. For example, Scribes A and D can be seen to have worked closely together, their hands alternating throughout the books of 2 Esdras to 4 Maccabees. Throughout the manuscript we find evidence of pages being removed and replaced and various ad hoc attempts to cover up previous mistakes. Despite seeming on the surface to be incredibly neat and organised, the composition of Sinaiticus was an astoundingly complicated operation.

What is a singular reading?

So how does a researcher get a manuscript to yield its secrets and help modern-day translators on their quest for accuracy? One of the tools at hand is a method of textual analysis called “singular readings”. This focuses on the unique readings in a manuscript: that is, variations in the text that are only found in that single manuscript and not in any other. As scribes copied from their source text, or exemplar, they naturally created variations between their text and the original, mostly accidental but sometimes intentional. These could be spelling mistakes, synonyms or changes to word order. In the most part these variants don’t affect the meaning of the text. Jongkind describes it in this way: “A relatively small number of these variants have an impact on how we will read a sentence of a paragraph. Yet the ripple-effect of such a variant becomes hardly noticeable when we look at the text on chapter or book level.” Singular reading isn’t entirely foolproof — it will inevitably exclude variants which appear in other manuscripts, and include any variants the scribe copied faithfully from their exemplar — but it is thought that these two categories of errors will generally compensate for one another.

Using this method the researcher begins to see the working practice of a particular scribe. Were they careful or slovenly in their spelling? Did they aim to roughly convey the general meaning of the text or vigilantly reproduce it word for word? In the case of Codex Sinaiticus, where we can compare the work of several scribes within a single manuscript, singular readings have proved to be particularly effective and have helped us get to know the scribes who had a hand in creating it.

One example of this is found in the book of Psalms. The copy of Psalms in Codex Sinaiticus was written by the same two scribes who shared the work from 2 Esdras to 4 Maccabees, A and D. The first 25½ leaves of the Psalms were written by scribe D, the remaining 15½ leaves by scribe A. In these pages scribe A is more careless and has double the number of singular readings. The singular readings also show that scribe D was somewhat prone to a phenomenon known as harmonisation, where a scribe would end up introducing variations in the text that come from other parts of the text with similar phrasing, or skipping ahead to a section where a phrase is repeated. For example, if you started copying down the sentence from Matthew’s Gospel “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” you might remember that in Luke’s Gospel, a similar phrase finishes “Kingdom of God” and you might write “God” instead. It’s rather like a cognitive form of auto-complete.

Understanding that there were three primary craftsmen behind the production of what remains of Codex Sinaiticus, and studying the scribal foibles of each, helps textual analysts to trace back variants to their source, and make evidence-based judgements about what the most accurate form of the text is likely to be. But beyond that, it also helps us to remember that the modern Bibles in our hands are links in a chain that is forged from the work of real humans, just like you and me, over thousands of years. The Bible isn’t just “here”; it was delivered to us down the ages through painstaking hours of human compilation, transcription, distribution, preservation, translation and latterly publication. Christians have always believed that God chose to deliver his word through real individuals: passionate yet frail, gifted yet fallible, some of whom paid the ultimate sacrifice for their dedication to their task. This human element isn’t something to be hidden away, an inconvenient truth, but rather celebrated, meditated on and marvelled over.